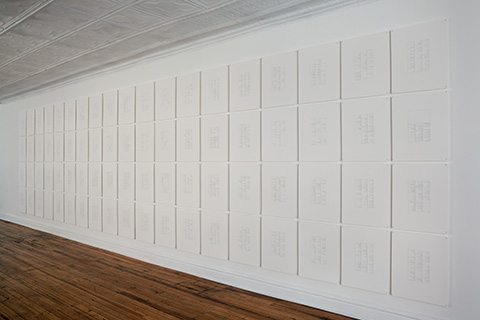

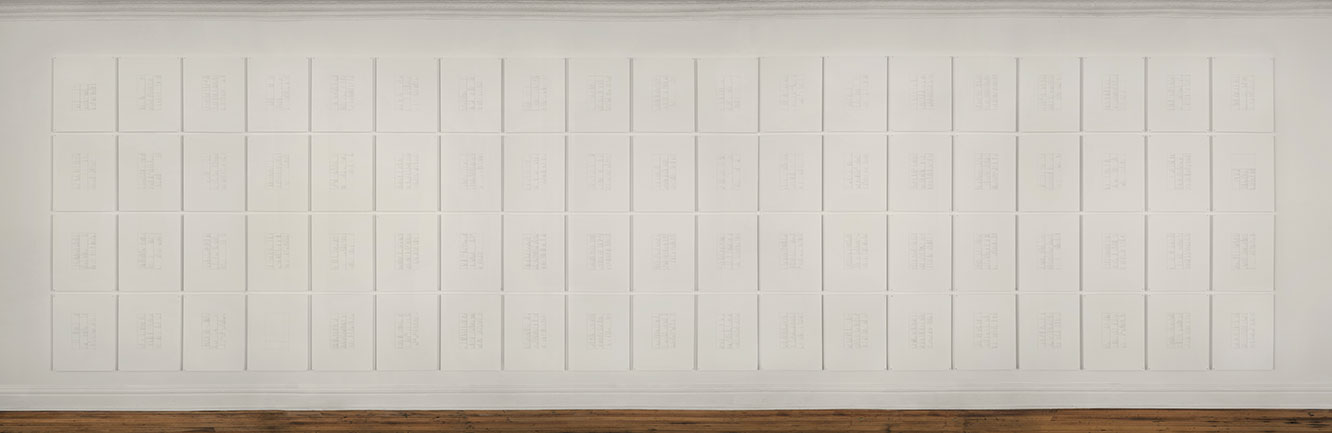

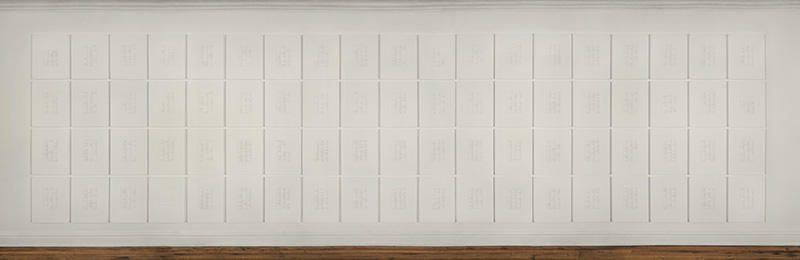

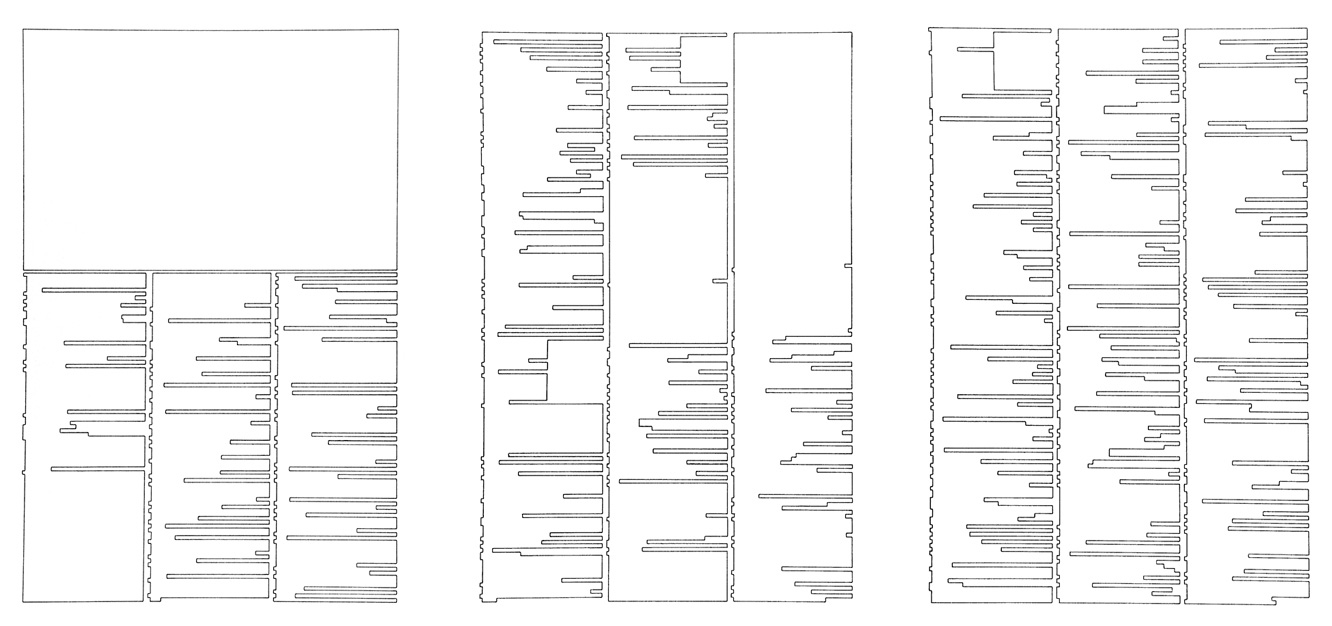

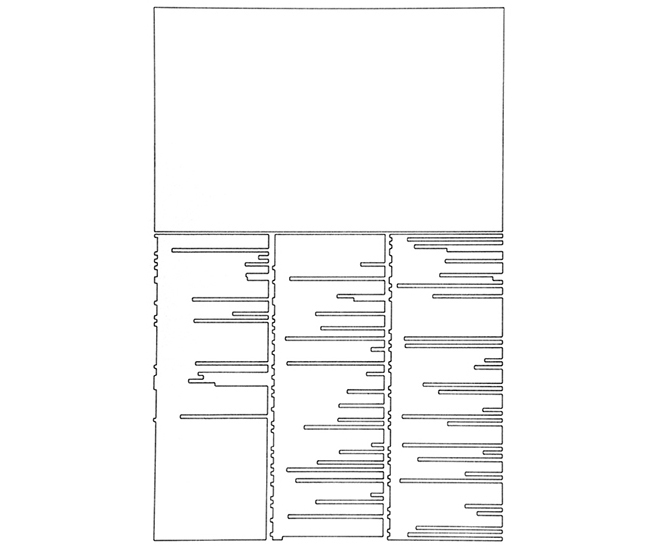

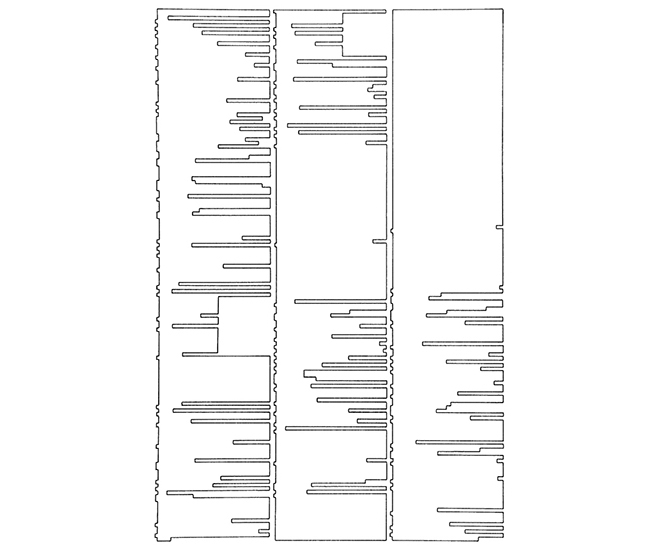

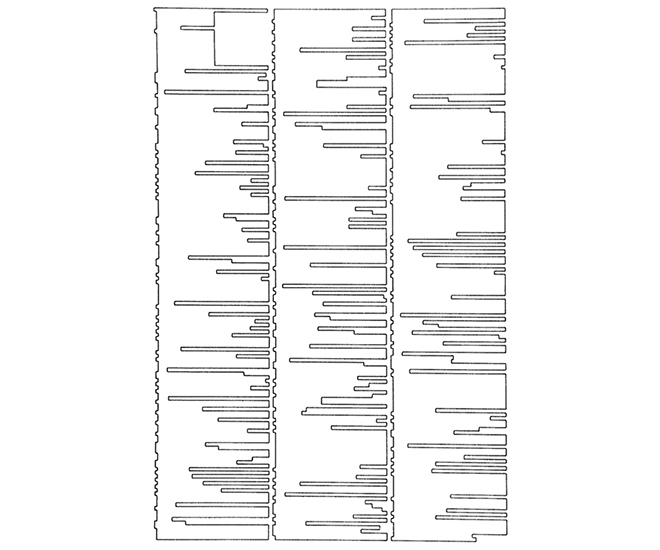

MARTIN BRIEF

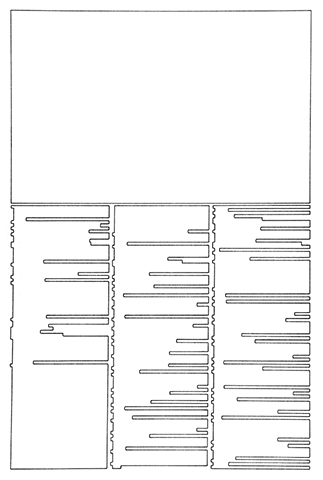

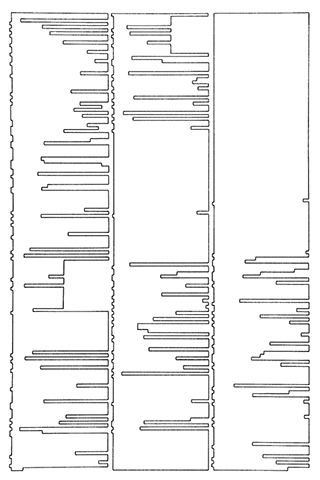

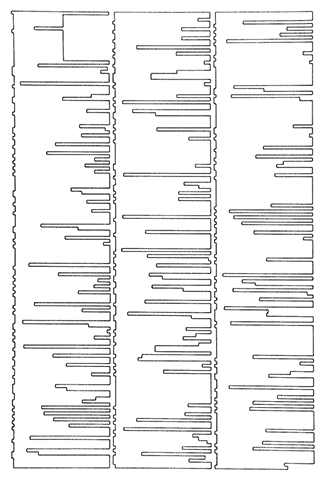

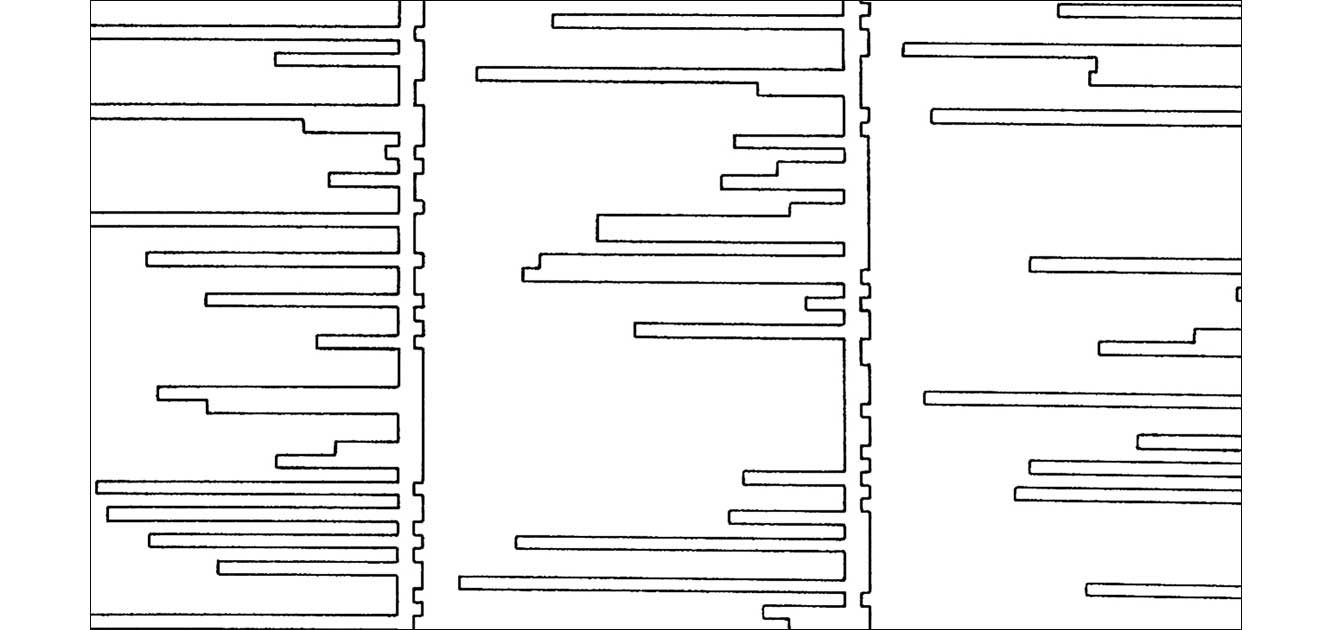

Dictionary

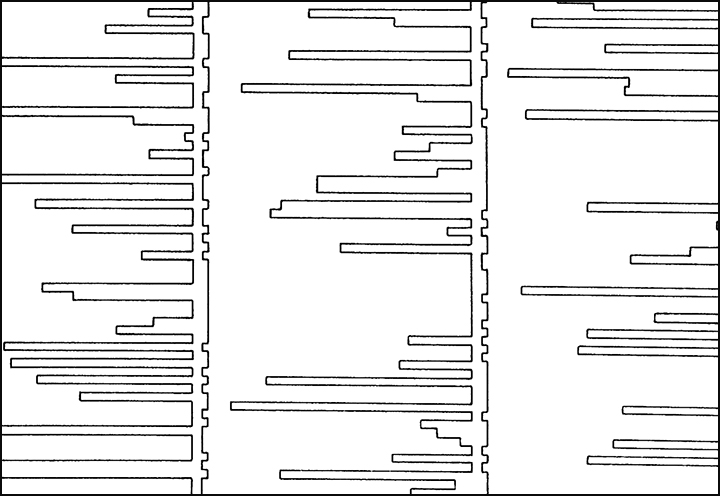

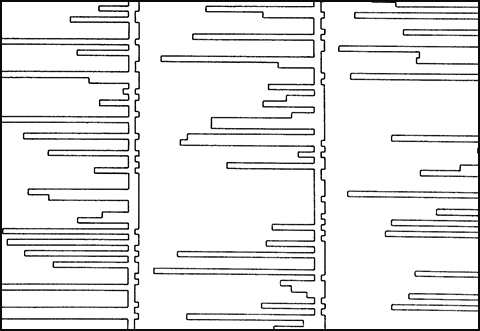

ink on paper, 11.5” x 7.5” drawing size, 24” x 19” paper size, 2006–ongoing

ink on paper, 11.5” x 7.5” drawing size,

24” x 19” paper size, 2006–ongoing

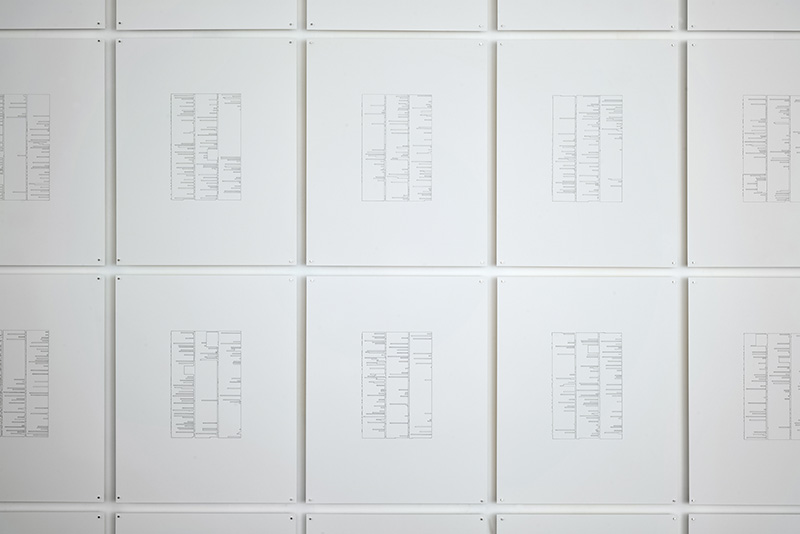

The drawings in this series are made by tracing the blocks of text on each page of the dictionary. The resulting line drawings define the space where the text had been. Begun in 2006, the ultimate goal of this project is to make a drawing for every page (2,662) of Webster's Third New International Dictionary. This project debuted at the Cité International des Arts in Paris. Installation views are from the exhibition A at beverly in St. Louis, MO. This exhibition included the complete set of the letter A, 155 drawings. Read an essay by Anna Fishaut

Tracing The Translucent by Anna Fishaut

The English language has a shape. This shape is an abstraction: a grammar of nouns linked to verbs; a network of derivatives tied to roots; a stratigraphy of old usage buried under new. It is a shape that can only be imaginary and never absolute, for the structure, over the centuries, has never been at rest. But the language has a geometry, too—one that allows a draftsman, should he choose, to capture and plot the language physically, in a momentary stasis. It is this geometry that Martin Brief concentrates upon; for him a collection of still points—the form that these points take—is a means to understanding a corresponding, finite shape: that of his own life.

Where to begin the collection? He begins with Webster's Third New International Dictionary and The New York Times, two sources of the language that filter ubiquitously through society. The first, an edition from 1966—the year of Brief's birth—is, at its core, a device for asserting the English language's limits. That which is contained within the dictionary's pages was an attempt at representing the entirety of what could be uttered and, in turn, understood in that year four decades past. The second, in Brief's open sample from 1966 and onward, is, perhaps first and foremost, a demonstration of the capacity for rhetoric to mingle invisibly with the neutrality that reported facts—the truth—seem to hold. News is of necessity always refracted through the non-neutral matrix of language; it is not only the content of the news that changes through the hours, days, and years, but also its linguistic context. Therefore, Brief seems to reason, if he can grasp the language's entirety by tracing it from A to Z, and if he can lay bare that which had previously seemed invisible—then language and the significance that it carries can be meaningfully plotted into concreteness.

In his Dictionary drawings, Brief has undertaken to trace each block of text from every page of his dictionary. The result is a set of drawings that, from across a room, look remarkably like the pages from which they were derived but that, up close, resemble something more akin to architectural schema, or measured heart rhythms. His Newspaper project is comprised of the remnants of single, selected front pages from randomly chosen dates. Each drawing is the visual detritus created when every typed "o" is filled in with ink and traced onto vellum, all else having been left behind within the degradable medium of never-drying ink and rapidly-decaying paper. The product is a series of quietly glowing, translucent pages that focus ever so softly into random pin-point shapes as one approaches. Each portion of each project requires the labor of careful and meditative—even obsessive—production. The Newspaper project, in particular, has no foreseeable stopping point; perhaps it will end only when the artist ceases to work. And so the question becomes: when Brief physically traces the dictionary in its 1966 totality, and when he systematically solidifies a portion of the daily news—over and over and over again—what does he hope to accomplish?

The answers to this question are varied, some seeming to suggest a linguistic strategy, others implying an apparently intentional ludicrousness. It is possible to envision that, when the dictionary has been fully traced, Brief will have circumscribed, and re-entered, the language into which he was born. It is the language of his mother and father; it is what, piece by piece, the utterable looked like at a moment of relative, personally significant stillness. And when The New York Times has been fully reduced to a set of circle-based schematic drawings, Brief will have replaced content with context. Any conceptual move back to the set of events that the title of each piece—the newspaper's date of publication—nods silently toward would have to be made by way of a re-hiding of the language, a process that itself would make one only more aware of the form/content duality. As it stands, each element of this series is a demonstration of how one can touch the past not through visual memory through photographs or representational drawings, for instance—but by understanding how that past was spoken of at its present. Gathered together, the Newspaper drawings change from still to animated. From his birth up to Brief's current instant, no two events, and no two linguistic representations of those events, have been the same. They are, in a sense, an analog of an autobiography—albeit one arrived at in an idiosyncratic manner, by the development of a quirky yet standardized system, and by taking the minutes, hours, and days required to carry this system out.

But it is evident that, in envisioning these series, Brief wishes to accomplish something outside of language, too, something that involves schematizing not language's complexities but, instead, the ineffable. The tasks he has undertaken verge on the absurd: the idea of tracing 2,662 pages from a dictionary that happens to have been published the year of his birth is as laughable as it is awe-inspiring; the practice of endlessly filling in each "o"—a seemingly perfect receptacle for the ink of an obsessive practitioner—is as puzzling as it is fascinating. If Brief is schematizing language's geometric intersection with his own life, he is also plotting wider concerns and broader concepts, ones that can only become clear as absurdity and signification converge upon one another but never actually touch: the fact that any life relates only randomly to another; that each event on any particular day occurs and then vanishes, apparently arbitrarily affecting one set of people while eluding others; that a person's life can only be preserved by way of its various remnants; that the written is never the same as the uttered and that the uttered can never be experienced more than once; that, finally, schematization disrupts any system it aims to elucidate and that, therefore, to trace is to obscure and to plot is to destroy.

Considering both linguistic strategy and organized absurdity, there are elements of both series that look back quite consciously to the Conceptual production of the 1960s and 70s. As the traditional art object was coming to seem more and more superfluous, artists began treating "art" as something much more undefined and ephemeral: events documented by photography, social commentary disguised as demography, visual investigation of language's relationship to what it represents, or targeted demonstration of rampant meaninglessness—these last two concerns seeming most relevant to Brief's own project. In 1971, for example, the artist Hanne Darboven transcribed a portion of The Odyssey by hand. The resulting fourteen-panel installation emphasized Darboven's handwriting, the drawn-out process of writing itself, and the abstract appearance of script on a page as much as it highlighted the traditional content of the epic poem. And in the late 1960s Bruce Nauman commenced a series of humorous, video-recorded activities—for example, Stamping in the Studio (1968) and Wall/Floor Positions (1968)—that served to disrupt an implicit tie between the completion of a task and the logic of its ever having been undertaken in the first place.

In recent years numerous artists have created works that seem to incorporate and reconsider the questions posed by Darboven, Nauman, and others. In 1993, Ann Hamilton created the installation Tropos, which included an activity that replaced the reading of lines of text with their procedural burning by a soldering iron—a process that transformed each page into an abstract remnant. And Rachel Whiteread, much less of a performer than a creator of resolute objects, has solidified the actual, physical points where books meet air Untitled (Pulp), 1999; Holocaust Memorial, 1995/2000, where bodies and lives intersect with the invisible, negative spaces that they create around them.

Brief's series are certainly related to all of these works, though they are by no means equivalent to them. He is in a sense maintaining the project—begun by others in his own formative years—of investigating how language conveys meaning, and how closely it can come to standing alone, without reliance upon content. He is continuing to ask why a work of art's purpose and meaning need be evident or even existent. And he is still wondering how written words and the traces of their presence and meaning, or lack thereof, relate to what makes any human life significant. When Brief has finished a work there are no visible words left to deconstruct, and language has become only part of the larger goal of self-definition achieved by circumscribing texts that relate to his own lived minutes, hours, and days. Instead of words there are quiet, tangible, and abstract art objects in the most traditional sense—thin outlines and circles on equally thin paper—meant to be collected and saved.

These objects are momentary stillness made manifest. They are what remain when an artist sets out to learn by doing, to comprehend by tracing, ad infinitum.

Anna Fishaut received her Master's Degree in Modern and Contemporary Art History from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago