MARTIN BRIEF

Newspapers

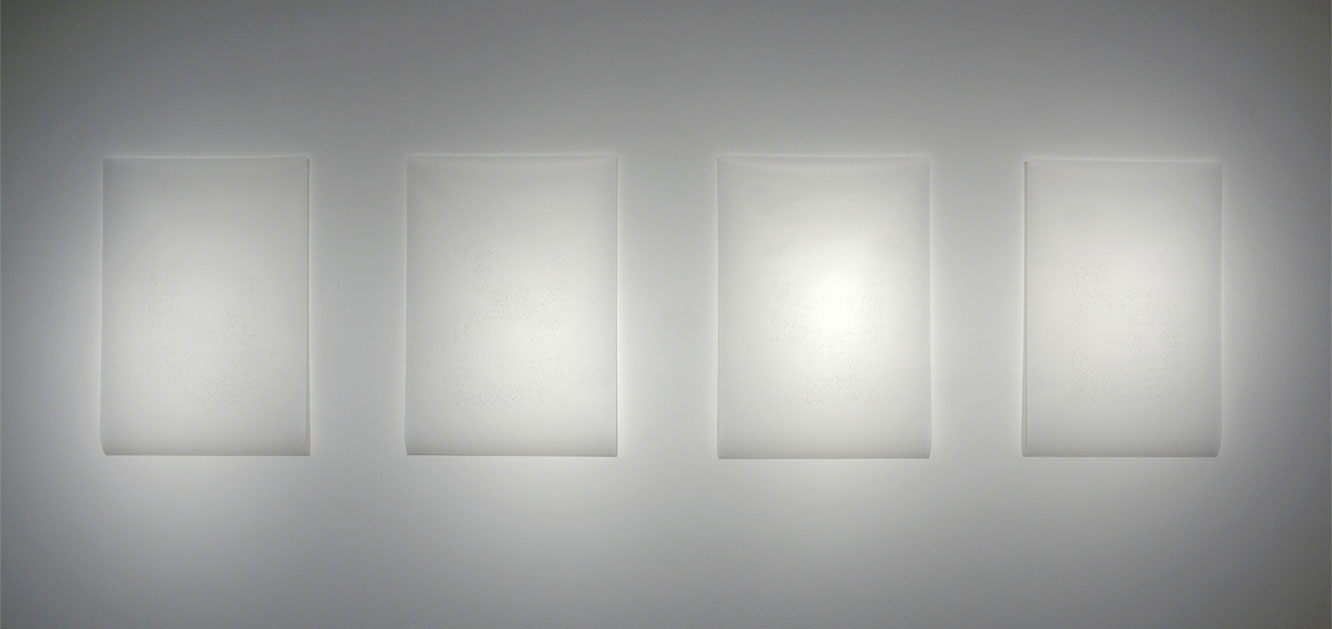

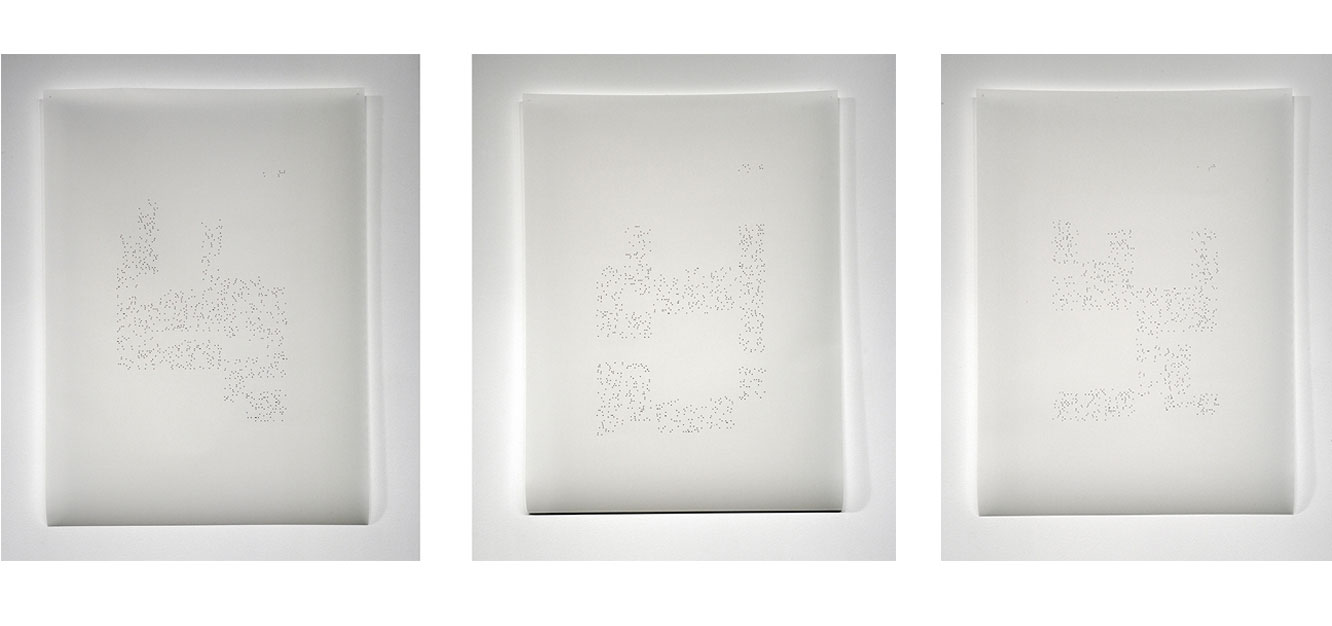

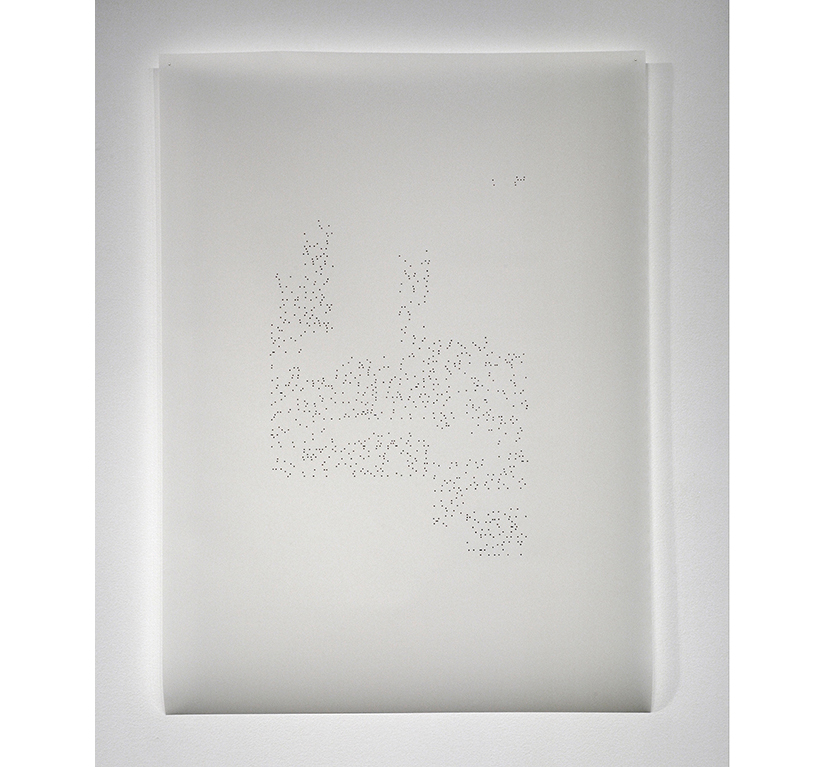

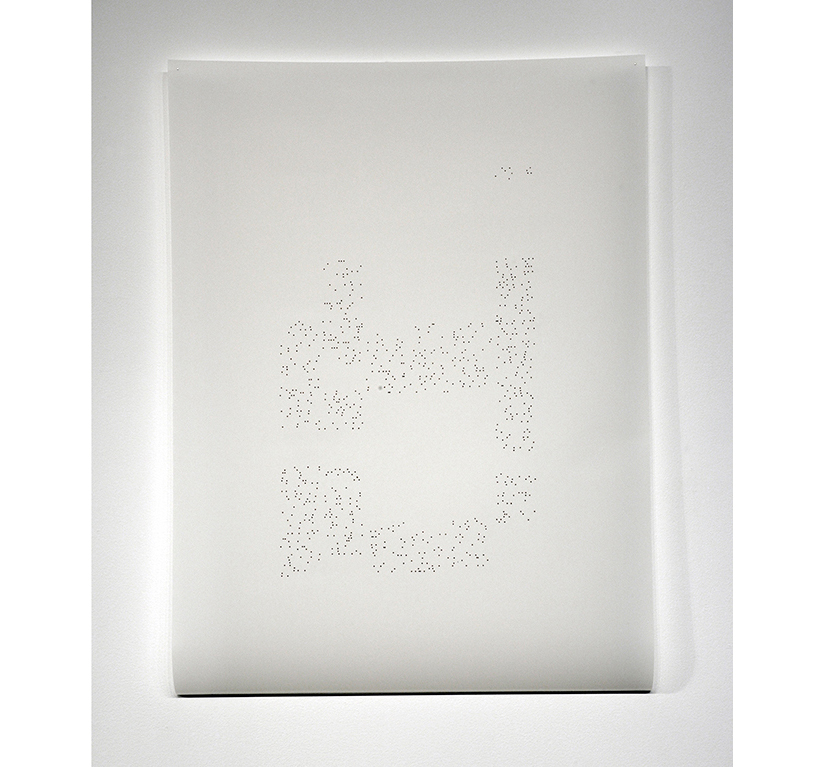

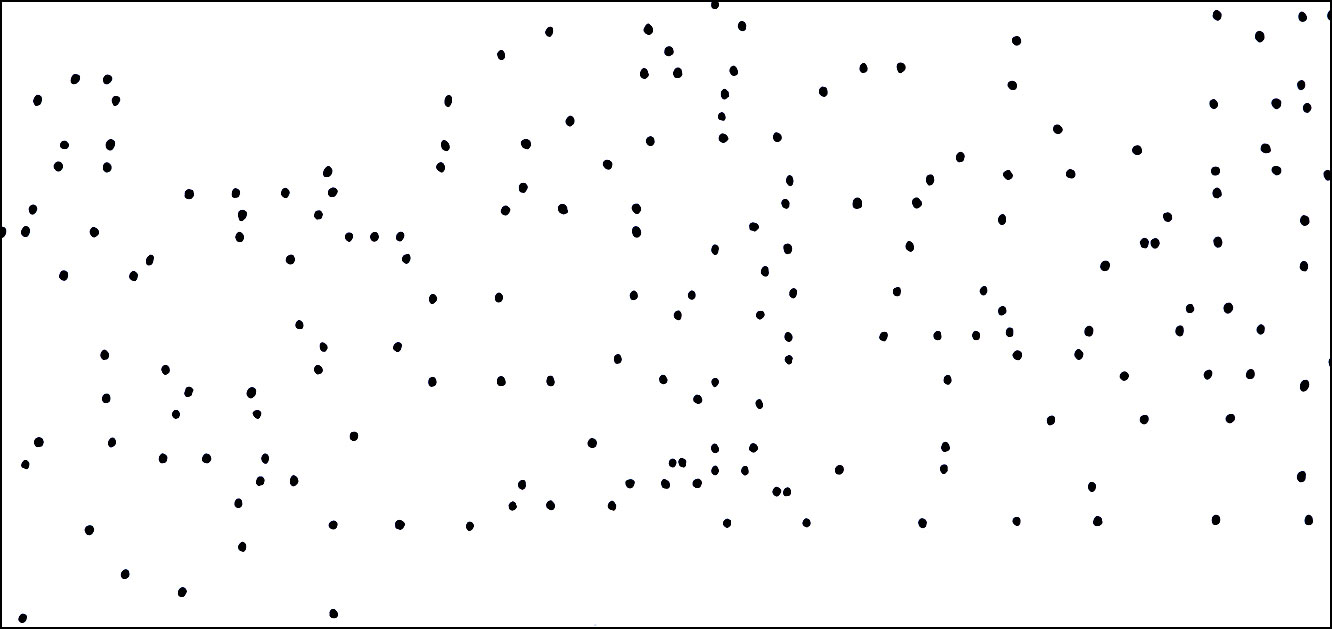

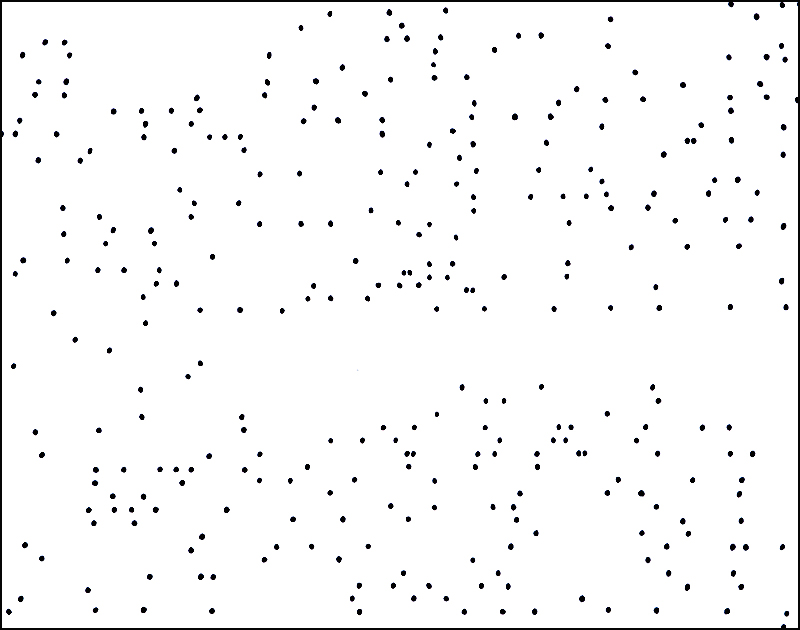

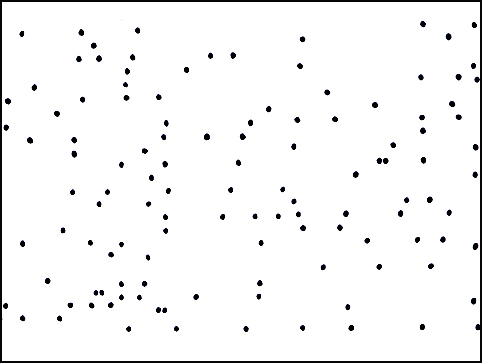

ink on paper, 33” x 24”, 2006–ongoing

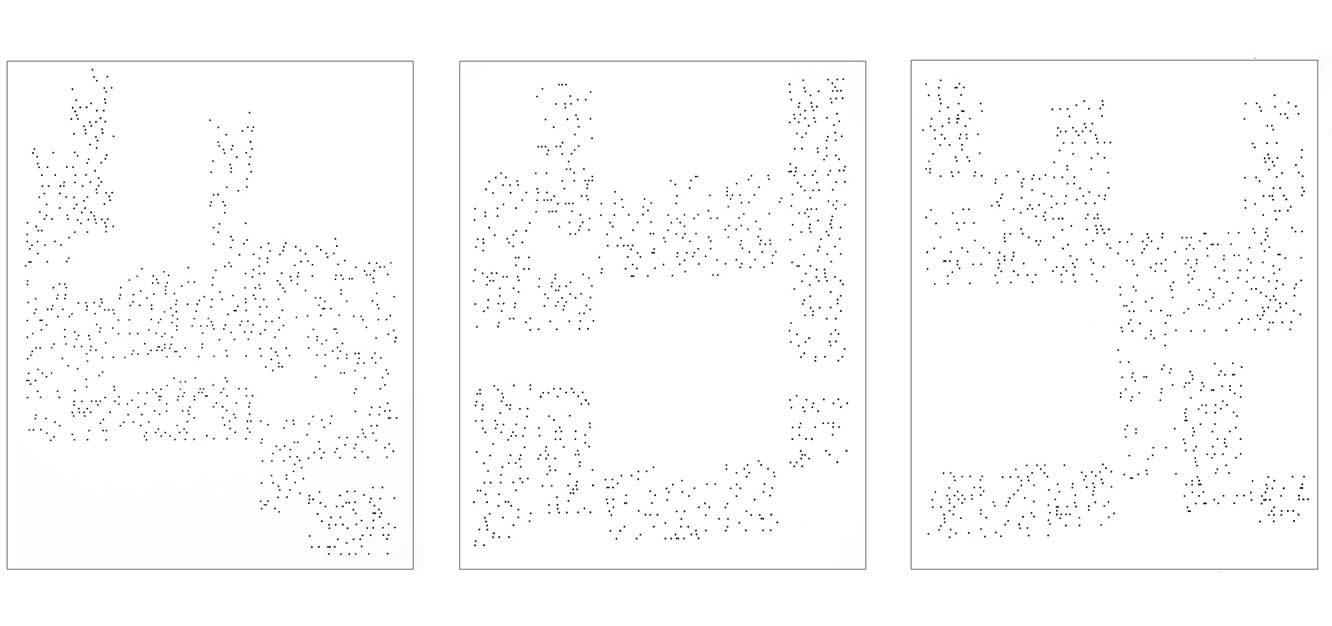

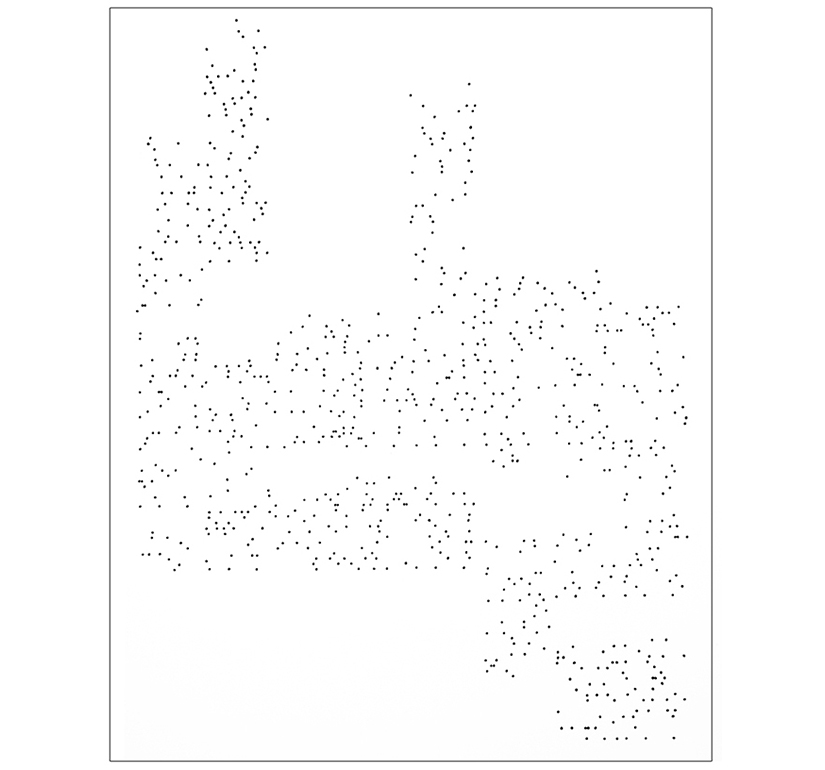

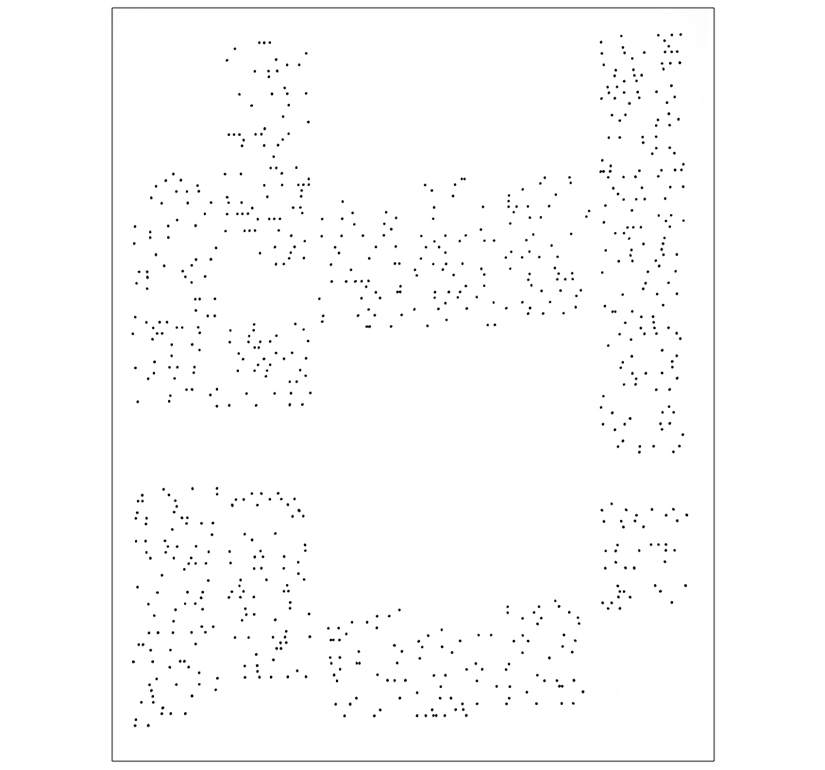

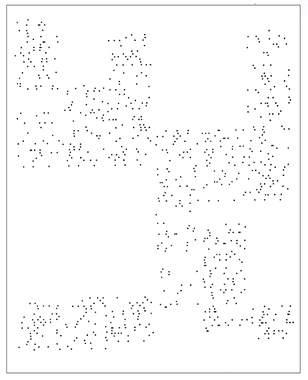

This series of drawings is derived from the front page of randomly selected issues of the New York Times. The title of each drawing refers to the date of the paper from which it was made. The drawings are ink on vellum and are created through the mindless, meditative act of filling in the center of each letter "o" in the text. This is an ongoing project begun in 2006. The dates of the drawings are randomly selected from the day I was born to the present day. The project will be complete when I randomly choose my birthdate. Read an essay by Kriston Capps

Finding Noise In The Signal by Kriston Capps

Where do we stand at the start of the third millenium, just moments after the dawn of the information age? Are we in a position to fully evaluate the advance—the greatest since the invention of movable type—by which the written word finally caught up to the evolution of radio and television and likewise took to the ether as data? Bathed in a perpetual stream of information, our civilization has achieved an unprecedented perspective of the globe in continuity. Yet like light refracted through a lens, that perpetual signal is subject to noise and manipulation.

It is the manipulation of information that makes the foundation for Martin Brief's work, both in content and in form. In The Newspaper Series, Martin Brief finds the noise in the signal. By abstracting ink drawings from the front page of the New York Times, the paper of record, he signals the imperfect and tenuous situation of readers—as citizens, as information receptors—who live in a political climate in which the codification of information is as vital to the distribution of power as news content itself. With this project, Brief has set himself a conceptual task, the result being that he reveals and obscures the artist as he manipulates the text.

Taken in their total, Newspapers are enough to give a viewer a sympathy headache. Brief's task is that rote: transferring and bubbling in each letter "o" from a Times's front page (the date randomly selected from the artist's birthdate to the present) onto a page of vellum, ad nauseum. Every successive day adds to his Sisyphusian chore. Yet for a tedious, repetitive gesture, the assignment could hardly be said to be mindless. Brief forcefully reveals himself as a cataloguer of information, a mediator of the text, even though it overwhelms him. The viewer imagines him performing this "close reading," considering vowel by vowel every carefully parsed and mediated word that makes up the news—reading, and digesting, the argot of journalism (and of politics, and of events themselves) in their countless configurations. Terror, terrorist, combatant, Islamofascist. House committee, subpoena, government. Washington.

Brief's explicit political rendering is obscured—as is the artist himself—by his abduction of sheer data from news. Brief is obedient to the news medium, which exists today beyond newsprint as information streamed over the ether. While arbitrary, his selection of the letter "o" is especially significant, making for drawings that casually resemble ballots, punchcards, and standardized testforms—that is, encrypted datasets that must be decoded. The only indication of the original content that persists into Brief's drawings are the dates given in the works' titles (e.g., March 25, 1975), a nod to On Kawara's date paintings. In Kawara's works, it's possible to glean clues about the artist's state at a given timeÑanyone who has seen many of them has sensed strife in colors governing a certain period, satisfaction in others, and so on. Brief's date drawings, in contrast, are further abstracted still and are all the less forthcoming. As with Kawara's work, the singular focus in The Newspaper Series remains on the artist, whose hand has collated the information—but in Brief's work, the artist has gone missing. Or rather, Brief presents himself as he stands vis-á-vis the Times (that is, in relation to the news, the world itself): as reader, receiver, data point, statistic.

The sense of frustration inherent to this relationship between text and reader finds a parallel in the works of Samuel Beckett. Beckett signaled the absurdity of modernity by burying his narrators under layers of language, contradiction, and misdirection. His Texts for Nothing, to consider one example, finds the story's narrator anticipating "desinence," a word Beckett chose to convey closure. (Desinence means, specifically, the inflected, grammatical termination of a word). Meaning is not to be found in Beckett's text but rather is the text itself. Similarly, in both The Newspaper Series and The Dictionary Series, Brief explores language at its termination point: indeterminacy.

And Brief certainly shares with Beckett a penchant for the absurd; the repetitive, obsessive nature of Brief's drawings, of course, rhyme Beckett's logorrhea. Brief's absurdity extends to Beckettian wordplay with puns, too: For The Dictionary Series, Brief seeks to "define" the words in the dictionary by tracing the jagged outline of the entries on the page. By examining the space within which dictionary terms superficially operate, he spurs the notion that meaning is fixed in a prescriptive way.

Progressing, again, page by page and letter by letter—from A to Z—Brief draws attention to the perverse manipulation of language today. Concepts in our language—such as "evil" and "freedom"—are by their nature fluid, having literary, historical, and moral implications that limit their usefulness in the public square. Yet these words have been pressed into service and assigned new, fixed meanings; indeed, the construction of language is a political project. Brief responds in his dictionary transcriptions, in which words have been emptied literally of their meaning.

Brief's longterm (and nearly limitless) projects situate his work alongside task-based, zealous "outsider" art. The Dictionary drawings, whose permutations are dictated by and extracted from the shape of the text, also recall a number of Conceptualist and post-Minimalist projects and artists. In creating a derivative surrogate for the dictionary text, governed by specific rules and accomplished through repetitive processes, Brief channels Bruce Nauman's wordplay and body surrogate pieces. The outlined text contributes to an archive of the artist's activity and focus.

Visually, the drawings most viscerally suggest Rachel Whiteread's Untitled (Library), in which the artist cast the negative space of library stacks using dental plaster. Brief's process is similarly calculitic, as if he is transforming words through mathematic integral and derivative functions. Ultimately, it is this nuanced, experimental basis to his works that give both series a Conceptualist context.

Kriston Capps is a staff writer at CityLab. He writes about housing, architecture, design, and other factors that shape cities. Previously, he was a senior editor at Architect magazine.